Material Selection for Optimal Metal Bending Parts

Matching Alloy Properties to Application Needs: Stainless Steel, Aluminum, and Titanium Considerations

Choosing the correct metal alloy makes all the difference when it comes to successful bending operations. Stainless steel stands out because it resists corrosion so well and maintains its strength even after countless sterilizations, which is why hospitals rely on it for surgical tools. Aluminum works great in aircraft manufacturing since it's light but still conducts electricity efficiently, something that matters a lot when every ounce counts. Titanium takes things further by offering unmatched strength relative to its weight, making it perfect for parts that need to handle heavy loads without breaking down. Working with these materials isn't straightforward though. For instance, stainless steel needs strong press brakes and tough tooling due to its resistance to deformation. Aluminum requires smooth dies or coatings to avoid scratching during forming processes. And then there's titanium, which gets temperamental if not handled properly in controlled conditions with special lubricants. When manufacturers pair wrong materials with their intended uses, problems happen fast. Take copper alloys versus zinc ones - the former bends nicely into tight curves while the latter tends to crack under similar stress.

Thickness and Bend Radius Constraints: Gauges, Springback, and Minimum Flange Rules

The thickness of materials plays a major role in determining what level of precision can be achieved and what kind of tools are needed for the job. When working with thin sheets below 0.5 mm, manufacturers can create very sharp bends, though there's always the danger of buckling or tearing if proper support isn't provided. On the flip side, plates thicker than 6 mm demand heavy duty presses and specially made tools just to get started. For most metals, the inside bend radius should be at least equal to the material thickness. However, stainless steel often needs twice or even three times that amount to prevent tiny cracks from forming, particularly with cold rolled varieties. Springback remains a critical factor too. Aluminum tends to spring back between 15 and 20 degrees after bending, whereas stainless steel usually springs back around 8 to 12 degrees. This means operators need to intentionally overbend parts to compensate. Another important consideration is flange length, which generally needs to be four times the material thickness plus the bend radius to avoid distortion when shaping. Fabrication Quarterly reported last year that about 22% of all production delays stem from ignoring these basic guidelines.

The Critical Role of Temper and Grain Direction in Real-World Metal Bending Parts Formability

The temper of aluminum has a major impact on how well it can be bent. When working with annealed O-temper aluminum, we typically see full 180 degree folds without any cracking issues. But things get tricky with T6 tempered versions which tend to crack around the 90 degree mark because they're just not as ductile. Grain direction matters too. Bending across the grain lines actually reduces the chance of fractures by about 70 percent compared to going along the grain, according to those ASM Handbook numbers everyone references. The problem comes when there's inconsistent grain flow, something that happens quite often with extruded or rolled stock that wasn't properly aligned for forming operations. This leads to all sorts of problems with uneven stress distribution and weird deformation patterns. We've seen this cause bracket failures during automotive stress tests time and again, usually traced back to poor grain alignment control. For parts where failure isn't an option, always go with ASTM certified materials that have proper documentation on their grain structure. And whenever possible, make sure bends are oriented perpendicular to the grain flow. It might seem like extra work, but it saves headaches down the road.

Design Geometry That Ensures Reliable Metal Bending Parts Production

Flange Length, Bend Allowance, and Flat Pattern Clearance Essentials

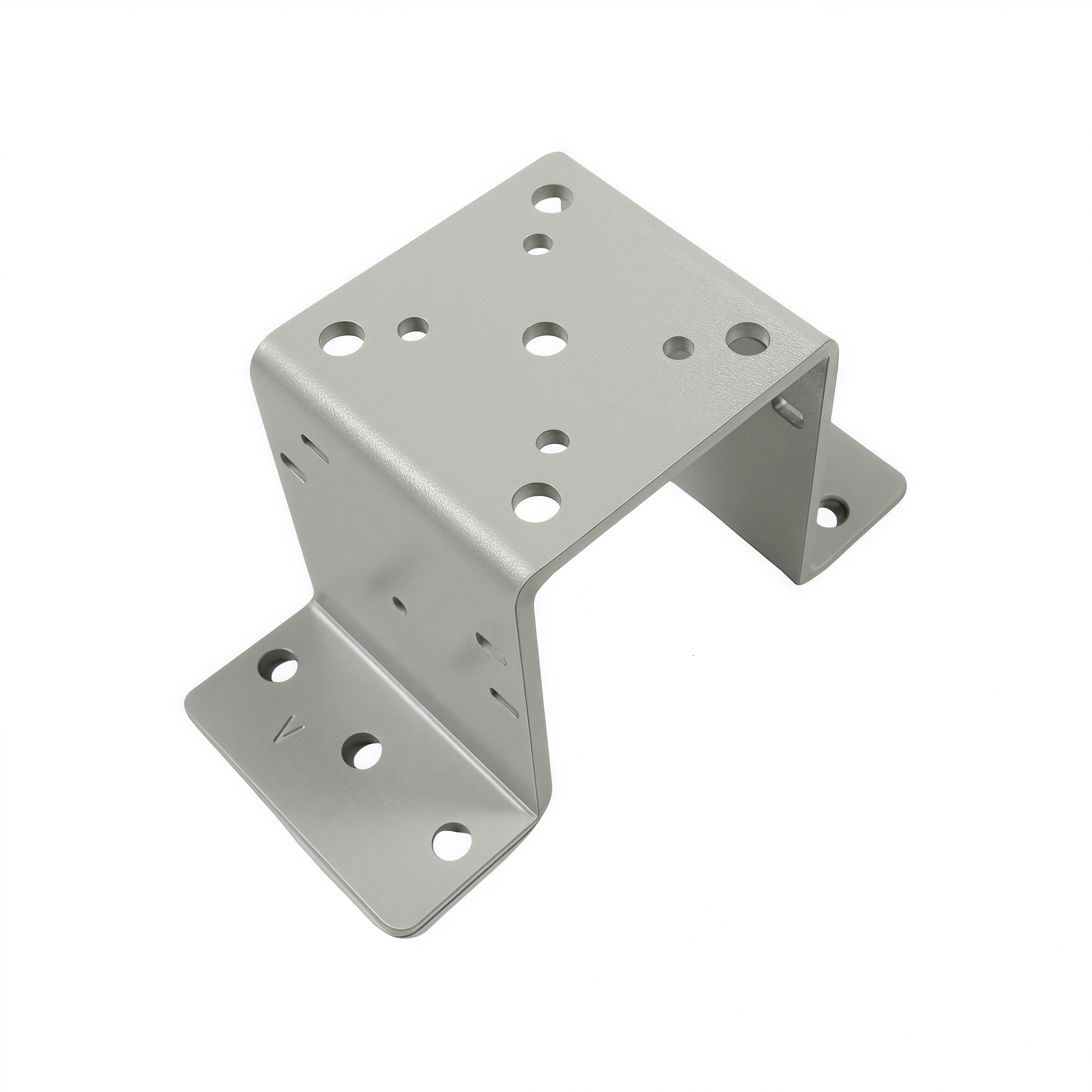

Getting the geometry right from the start saves money in the long run. When it comes to flange lengths, most people know about the 2.5x rule but that's actually not enough. The safe bet is at least 4 times the material thickness plus the bend radius. Take 2mm stainless steel with a 3mm radius? We're looking at around 11mm minimum flange there. Now for bend allowances, air bending usually needs about 1.5 times the material thickness because metals stretch and compress differently along their neutral axis when bent. This matters a lot for developing accurate flat patterns. Also important: leave about 3 to 5 mm space between features on the flat pattern to avoid tool clashes during manufacturing. Manufacturers who standardize their bend radii across parts see real benefits. Industry studies point to roughly 30% savings in setup costs compared to parts with varying radii. And don't forget to check those digital flat patterns against actual prototypes first. Small tolerances can stack up fast in production runs, leading to big problems down the line.

Preventing Common Failures: Corner Relief, Die Interference, and Bend Line Placement

Making smart changes to part geometry really makes a difference for reliability in production. Those corner relief notches we talk about so much? They're basically 45 degree chamfers that go about 1.5 times deeper than the material thickness itself. These little features help spread out stress at those tricky T-junction areas, which cuts down on cracks forming during fatigue tests by roughly 60%, according to lab results. When working with dies, it's important to leave at least 4mm space between any bend line and nearby edges or other features on the part. For holes and cutouts, they need to sit no closer than three times the material thickness away from bends to keep them round and dimensionally stable after forming. The order in which bends happen also counts for something. Complex parts are usually best formed starting from the center and moving outward, otherwise already bent flanges might block access for tools later on. Grain orientation plays into this too. Parts bent against the grain tend to hold their shape better overall, but sometimes aligning bends with the grain direction gives nicer surface finishes and less variation when springback occurs. This approach works well for precision components, although preventing fractures still takes priority in most real world manufacturing situations.

Bending Process Selection and Its Impact on Metal Bending Parts Quality

Air Bending vs. Bottoming: Trade-offs in Tolerance, Repeatability, and K-Factor Consistency

Air bending works by pressing materials against a V-shaped die without letting them fully settle at the bottom. The angle formed depends on how deep the punch goes into the material. This method gives manufacturers quite a bit of flexibility since they can get multiple different angles from the same die setup, plus it cuts down on tooling costs. That makes air bending especially good for creating prototypes or running smaller batches of parts. But there's a catch - because this technique relies so much on how the material behaves, results can vary between batches. Typical angular tolerances hover around plus or minus half a degree, and factors like material thickness changes, temper variations, and springback effects cause the K-factor to shift from one production run to another. Bottoming, sometimes called coining, takes a different approach by forcing the material completely into the die cavity with heavy pressure that pushes past the elastic limits of the metal. This creates much tighter control over angles, usually within about a tenth of a degree, along with more consistent K-factors and better part-to-part repeatability. These qualities make bottoming essential for high precision manufacturing needs. While bottoming does require separate tools for each specific shape and tends to wear out equipment faster, many shops find the investment worthwhile whenever exact dimensions and reliable processes are absolutely necessary for their operations.

FAQ

What materials are best for metal bending operations?

Stainless steel, aluminum, and titanium are excellent choices due to their unique properties suitable for various applications, such as corrosion resistance, lightweight, and strength-to-weight ratio.

How does material thickness affect the metal bending process?

Material thickness influences the precision of bends and the type of tools needed. Thin sheets allow for sharper bends, whereas thicker plates require more robust equipment.

Why is grain direction important in metal bending?

Bending across grain lines reduces fracture chances and provides better stress distribution compared to going along the grain.

What are the differences between air bending and bottoming?

Air bending offers flexibility and cost savings with variable angles, but results vary by batch. Bottoming ensures precise angles and consistency, ideal for high precision needs.